The Tortoise and The Hare

In Aesop’s fable, a hare races a tortoise. The tortoise is described as slow, steady and unwavering in its pursuit of the goal, and the hare – though it is fast and brash – becomes overconfident and loses to the tortoise. This classic tale offers a perfect metaphor for why our investment philosophy focuses on quality – particularly when considering investing in banks.

Banking is one of the few industries where there is no long-term advantage for shareholders in moving fast. The lending and borrowing of capital is fundamentally a commodity business. What counts is how a management team controls its assets, liabilities and – most crucially – losses. Any errors made are magnified by the inherent leverage of the bank’s business model, which means shareholders’ equity can be easily and quickly wiped out.

In its simplest form, a bank makes money by taking deposits and then lending those funds to people who need them. Unfortunately, not every borrower will repay their loan and a bank therefore needs a cushion through which it can absorb losses while still being able to repay depositors.

This is where equity comes in – this is owners’ capital, including our clients’, other shareholders and management. It acts as a sponge to absorb exceptional losses after any money set aside for bad loans has been eaten up. For most banks, equity is small relative to loans, which means you have to be confident that bad loans (or other losses) won’t exceed equity – because if they do, the business you own becomes bankrupt and your investment drops to zero.

HDFC – Passing the ‘Marshmallow test’

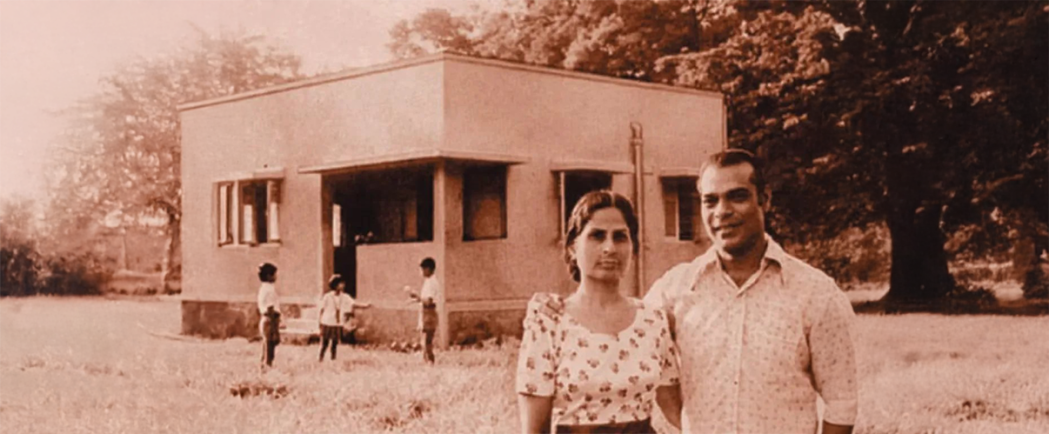

Success in banking is usually built on a culture and institutional temperament that can prioritise profitable growth. The emphasis here is on the word ‘profitable’, because although any banker can grow loans – not everyone can do it profitably. One only has to look at a share price chart (see figure 1) of what at its peak was India’s fourth-largest private sector bank1 – YES Bank – to understand this phenomenon. There’s a reason we don’t invest alongside the “banking hares” in emerging markets.

Figure 1: YES Bank since inception shareprice (INR) ©HDFC Bank Limited

The problem with banking is that there is a timing mismatch between loan growth and the losses that might accrue from loans that are not repaid. Near-term profitability and earnings-per-share growth can be an illusion; instead, a bank needs leaders who would pass Walter Mischel’s marshmallow test. This famous 1972 Stanford experiment measured how well children could delay gratification to receive greater rewards in the future, by offering them a choice between one small but immediate reward, or two small rewards if they waited for a period of time. Two individuals who would undoubtedly have passed this test are H.T. Parekh, who founded HDFC Ltd in 19772, and his nephew Deepak Parekh, who was at the helm of the business for over 30 years and was responsible for the leadership and culture that led to its success.

Over the decades, HDFC Ltd carved out a reputation for prudent decision-making, disciplined growth and resilience during times of market turbulence. Just how beneficial this culture has been for shareholders can be seen in the corporation’s cumulative loan losses in the full year before the announced merger, which stood at 28bps of cumulative loans paid out since its inception in 1977. This highly differentiated lending culture resulted from a thoughtful and deliberate approach to risk management and customer relationships.

HDFC Ltd thus built a lending model that stands out in the Indian financial landscape. The culture that underpins this approach provides stability and reliability in a commoditised and cyclical industry positioned HDFC Ltd as a trusted partner for millions of borrowers seeking home loans.

Funding sources matter

HDFC Ltd was the parent company of HDFC Bank, which it founded in 1993 when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) allowed private businesses to establish regulated deposit-funded institutions.

This fundamental difference between the two businesses is an important one, because the right to take and hold retail deposits places more capital and regulatory restrictions on a bank than are placed on a business operating under a Non-Bank Financial Company (NBFC) licence, as HDFC Ltd did. The advantage of holding customer deposits, however, is that if a business has a strong branch network and a great brand, customer deposits can be a cheaper and stickier form of funding.

Importantly, the RBI has been levelling the regulatory playing field over the past decade, to encourage NBFCs to convert to banks. From a regulator’s perspective, non-deposit or wholesale-funded institutions (NBFCs) are a riskier proposition to the overall health of the financial sector because they are not limited by deposit growth to fund loans.

That means they can grow to become systemically important providers of capital to an economy or sector but can still be at the mercy of other lenders who might withdraw their funding overnight to ensure their own safety if the lenders’ loan losses look as though they might risk the underlying equity – as in the case of YES Bank, which operates under an NBFC licence.

For non-deposit-funded banks it is the fear of the losses rather than the actual losses that can lead to the demise of a bank. This issue is endemic to this type of business model, as witnessed with the failure of Countrywide in the United States and Northern Rock in the United Kingdom in 2008. These regulatory considerations were acknowledged by Deepak Parekh at the time of the HDFC merger. ‘The last 3 years has seen a host of guidelines issued by RBI on harmonising regulations between banks and NBFCs. These measures have considerably reduced the risk arbitrage which was there between a bank and NBFC’3. At its core, the merger allowed HDFC Ltd to transform itself into a deposit-backed bank.

A merger of equals?

The reverse merger of HDFC Ltd into HDFC Bank was completed in July 2023 and was initially celebrated by the markets – both share prices rose by 10% on the day of the announcement.

Image 2: Deepak Parekh at the announcement of the merger ©HDFC Bank Limited

It was initially seen as a win–win because the combined entity would benefit from HDFC Ltd’s dominance and expertise in housing finance and HDFC Bank’s better branch scale and distribution. In the longer term these benefits will likely accrue to shareholders of the merged business. That it was a reverse merger, though, is key to understanding the post-merger blues.

Near-term pain...

Before the merger, HDFC Bank had grown its book value at a compounded rate of 22% per year since FY 20114. In the year following the merger that growth rate fell to zero, as the combined entities’ return on assets fell below the bank’s historical norms – both on an absolute and a pro-forma basis. This was because of action taken by the management team to manage the bank’s loans-to-deposits ratio.

The loans-to-deposits ratio is an important metric for assessing a bank’s financial health and risk profile. It shows how much of the bank’s deposits are being used for lending. A ratio above 100% means a bank is lending more than it’s collecting in deposits, which isn’t ideal – it could put a bank at risk if the economy slows down or if deposits decrease.

After the merger, and as a result of it, HDFC Bank’s loans-to-deposits ratio jumped to 110%, up from its historic average of around 86–87%. Since then, and in line with the bank’s conservative attitude to risk-taking, the management team has prioritised lowering the loans-to-deposit ratio.

This has been achieved through a two-pronged approach – slowing down loan growth and taking on higher-cost long-term debt.

Before the merger, only 8% of HDFC Bank’s liabilities came from borrowings, with the rest from deposits. But after the merger, borrowings shot up to 21%. This means that for every 100 Indian rupees the bank owed, 21 rupees now came from borrowings, compared with just 8 rupees before. Raising this excess liquidity from borrowings is considerably more expensive than raising it from deposits, and HDFC Bank’s cost of funds increased from 4% to 4.8%. This is a significant increase in raw-material costs, which has impacted near-term profitability and led people to question whether the business is either too large to grow or is being outcompeted by the likes of ICICI or the State Bank.

...for long-term gain?

Although this slowdown in loan growth might seem concerning at first, as longer-term-focused shareholders we believe it should be welcomed as part of a broader plan to strengthen the bank’s financial health and allow it to take advantage of the industry tailwinds.

The real estate industry in India is expected to double its contribution to economic growth over the next two decades5, driven by increased urbanisation and a growing middle class. India’s urban population is expected to reach 600 million by 2030, and the home loan market is expected to grow at 15% per annum over the next decade, supported by rising incomes and government-backed initiatives6.

By focusing on growing deposits, taking a careful approach to lending and using securitisation, we believe HDFC Bank is setting itself up for strong long-term growth in the coming years. The plan outlined by the CEO Shashidhar Jagdishan is to grow conservatively in FY25, match the market in FY26 and then aim to outpace competitors by FY277. This gives the bank time to adjust to the merger without sacrificing long-term growth.

To finish first, first you have to finish

HDFC’s strategy is emblematic of the tortoise’s approach in Aesop’s fable: a slow and steady pace focused on long-term growth rather than chasing quick, short-term gains.

Taking this one step further, one could argue that its decision to prioritise the health of its balance sheet in 2024 while negatively impacting the income statement is entirely consistent with a culture focused on risk management and doing the right thing for long-term per-share growth of the business.

For the clients of our emerging markets strategy, HDFC is a quintessential example of how we believe the tortoise – through unwavering determination and a commitment to sound principles – wins the long-term investing race. As we continue to navigate the complexities of emerging markets, HDFC’s approach serves as a reminder that the most rewarding investments are often those that take the long view, one step at a time.

1. Gupta, S. (2024). YES Bank Restructuring, 2020. Journal of Financial Crises, volume 6, issue 2. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1560&context=journal-of-financial-crises

2. HDFC Annual Report (FY2022).

3. The Economic Times India (4 April 2022). RBI Notification triggers HDFC-HDFC Bank merger talks.

4. HDFC Annual Report (FY2024) and Skerryvore analysis, 2023.

5. The Economic Times India (19 October 2024). India’s real estate sector growth beyond 2024.

6. Global Property Guide (19 March 2025). India’s residential property market analysis 2025. www.globalpropertyguide.com/asia/india/price-history

7. The Economic Times India (19 October 2024). HDFC Bank sees pre-merger loan-to-deposit ratio in 2-3 years: CFO Srinivasan Vaidyanathan. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/hdfc-bank-sees-pre-merger-loan-to-deposit-ratio-in-2-3-years-cfo-srinivasan-vaidyanathan/articleshow/114378692.cms

Any information provided in this document relating to specific companies/securities should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular company/security.